📚 Stay up-to-date on the Book Club

Catch up on the latest Boston.com Book Club pick and join the virtual author discussions.

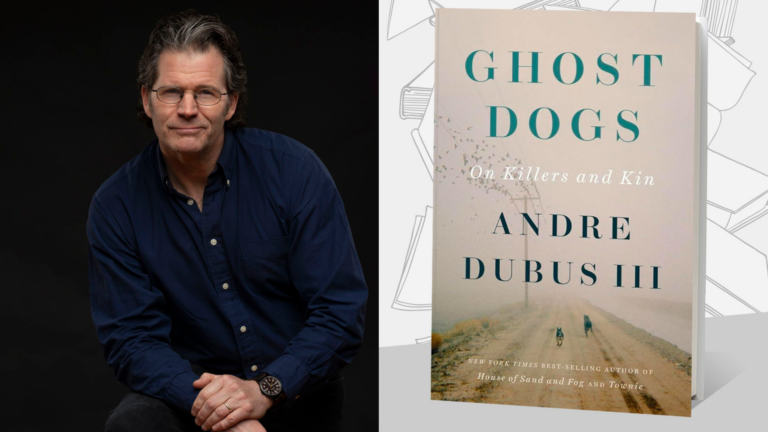

Andre Dubus III believes every life needs to be captured in some way. In his three decades as a writer, he’s mined his own life countless times, writing essays about his childhood, his relationships, and the sometimes wild detours he’s taken to get where he is now.

The culmination of those 30 years can be found in his latest book, “Ghost Dogs: On Killers and Kin,” a collection of more than a dozen essays that span his entire career.

“I’ll finish a novel or long story and then I’ll just feel a need to write about something straight from my life experience,” he shared at a recent Boston.com Book Club event.

In it, he writes about the time he was nearly shot by his father’s gun, what summers spent in the Louisiana bayou with his grandfather taught him about being a man, the fears he had when he learned his wife was pregnant with a girl, and the dogs that haunt him to this day. The essays are raw and imbued with a vulnerability, Dubus said is “simple, but it’s not easy” to capture.

If he ends a writing session feeling “nasty and vaguely inappropriate and naked” then he knows he’s done his job well.

“Just because we were there and we lived through it, I would suggest to you, that doesn’t mean we know what happened,” the author said. “That’s what I love about going back with the essay form and the memoir form. It’s a way to put those pieces back together.”

Dubus is the author of “Such Kindness,” “Townie,” and the National Book Award Finalist “House of Sand and Fog,” among other titles. He’s also well-known in the New England literary scene as a creative writing instructor at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, Harvard University, Tufts University, and Emerson College.

At our latest virtual author discussion, he was joined by Laura Lamarre Anderson of Lowell’s Lala Books to discuss his newest book, his writing process, and why he’s drawn to writing about tough subjects.

Read on for takeaways from their discussion, watch the full recording below, and sign up for more Book Club updates.

“Ghost Dogs” starts with an essay on fatherhood — his doubts about his own role as a father and a reflection on being an adult child without a father. Dubus discusses his worries about raising his infant daughter (now aged 28) in a patriarchal society that he feared would prey on her.

Throughout the book, the writer also returns to the process of building a house for his family. He shared how he came into money after the success of his third book, when his three children were still very young.

“I honestly thought, I’ve never had money before, God I could write all day and I’m just gonna write all day. Thank God my wife, Fontaine, made it clear that she wanted a home for our kids,” he said. “I didn’t know how much it meant to me. It meant far more than I knew to have a home to raise our kids.”

Guns feature heavily in this novel, both as an object of the writer’s fascination and hatred. He grew up with an appreciation for their craftsmanship, but had grown to see them as a tool of toxic masculinity and unnecessary violence.

“I shot my first gun at six and I had an appreciation for them as tools … but I detest them and I wish there wasn’t one on the planet,” he said.

In one essay, he shares a harrowing story about nearly being shot when his father’s gun accidentally goes off. At another point in life, it’s Dubus who almost shoots his brother. And in another piece, he has a difficult conversation with his elderly father-in-law about not allowing a gun in his home. Writing the essays allowed him to look back on those situations with more nuance.

“I think the province of literary art, which I aspire to, is the gray, is the nuance. There is no black or white. It’s all a big, beautiful, awful, but often beautiful mess. And so just capture it, just capture it.”

While he admits he’s never been surfing, he thinks about writing like trying to stay focused on a surfboard while “something larger than you is pulling you along.” It’s only after he gets out of that deep focus that he’s able to make sense of the emotions he’s excavated on the page.

“I do feel something, but it’s a high degree of concentration, trying to get into that trance state. It’s very pleasurable once you find it, as a lot of you probably know, but I don’t feel the emotions I’m trying to capture until I read it later.”

In the early years of his career, Dubus wrote while working multiple jobs as a teacher and day laborer. It took him four years to write his third novel, which he started when his wife was pregnant with their first child and finished as a father of three. In that time, he would find time to write even if it was only 15 minutes a day.

“I wrote 15 minutes a day in a car parked in a graveyard not far from my house. I taught four or five courses at colleges around Boston, in Boston, and remodeled houses, and didn’t sleep,” he said. “And it was a beautiful, rich, exhausting, but rich, rewarding life. But you know, I tell people whose lives are full as most people’s are, you can get a lot done in 15 minutes a day.”

When he first started writing about his life, he was hesitant to include any details about the people closest to him for fear of exposing them unfairly to the public. At the advice of fellow writer, Richard Russo, he thought more critically about his intention behind writing those stories.

Dubus said he realized he never writes any essay featuring a loved one with any anger or desire to settle scores. Instead, he’s “just trying to capture what it was like for me in that moment.”

“I think too many of us — for beautiful reasons, frankly, loving reasons, family loyalty reasons — feel we have to be the biographer of our families. And I would say no, you’re not the biographer of your family. It’s your turn, Sally Jones, to give the mic to 14-year-old Sally who never got to sing about that terrible summer.”

Catch up on the latest Boston.com Book Club pick and join the virtual author discussions.

Stay up to date with everything Boston. Receive the latest news and breaking updates, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.

Be civil. Be kind.

Read our full community guidelines.