Inside Connecticut’s Fight to Expand Medicaid Coverage for Undocumented Immigrants

In July, the state will expand coverage to undocumented immigrants under age 15. But it still falls short of advocates’ goals.

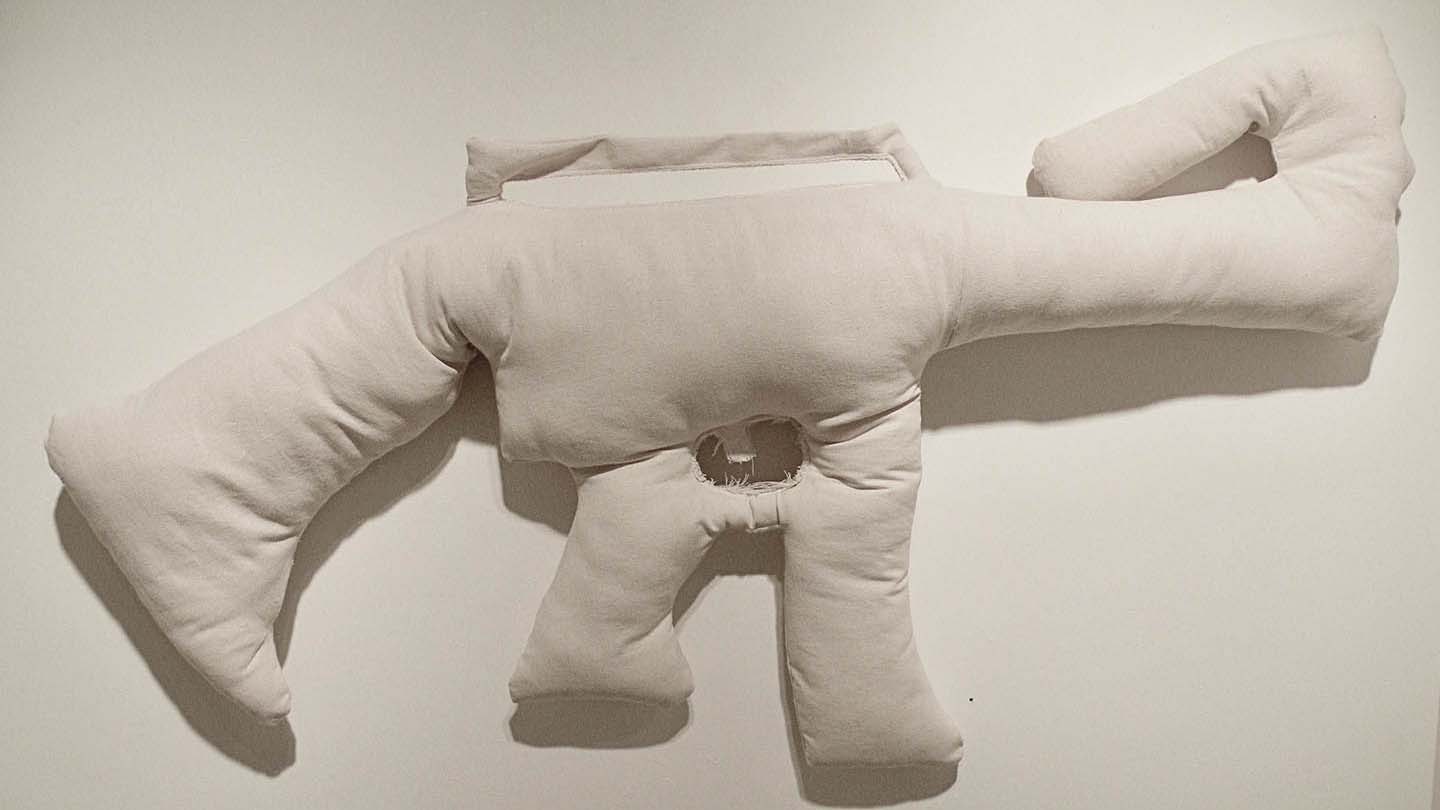

HUSKY-launch press conference with Senator Lesser and Representative Gilchrist in February 2024.

(David Vita)Darek Clavijo retired from soccer at age 9. The game wasn’t safe for him anymore. Too often, his breathless moments on the field would devolve into intense asthma attacks. Darek would struggle to breathe or move. His body would grow weak. It would feel as though his throat were closing and congestion had seized his lungs.

Darek visited a clinic for low-income patients, but left unchanged: no diagnosis, no treatment, and definitely no more soccer. After he caught Covid in 2020, his asthma grew even more severe. His sister, Najely Clavijo, recalled sitting next to him during attacks, scared that his lungs would give up.

As undocumented immigrants from Ecuador, his family had no health insurance—all they could do was wait and worry. “And then the law was passed,” Clavijo said.

In January 2023, Connecticut expanded Medicaid coverage to undocumented immigrants up to age 12. It was the first time undocumented immigrants of any age could qualify for coverage from the state. Anyone within that age range could enroll and keep their coverage until they turned 19. Darek, then 12, just made the cut.

The same week, Darek’s mother signed him up. After years of attacks, Darek was officially diagnosed with asthma and prescribed an inhaler. After not being able to see the board at school and suffering from eyestrain headaches, he also received his first pair of glasses.

Darek was just one of more than 9,000 low-income, undocumented children in Connecticut who have benefitted from this expansion. In 2021, Connecticut passed a bill to expand HUSKY Health—the state’s Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance programs—to include undocumented children aged 8 years or younger, effective January 2023. During the 2022 legislative session, the state added undocumented children aged 12 years or under. Most recently, in 2023, the state passed a bill covering undocumented immigrants up to age 15, effective this summer.

While these bills mark significant progress for children like Darek, they’re still short of advocates’ goals.

The bill proposed during the 2023 legislative session originally called for expansion to age 26—the age when all other young adults would be kicked off their parents’ health insurance, per the Affordable Care Act. But that bill was eventually lowered to age 15. “A cutoff of an arbitrary age does not make any medical sense,” said Julia Rosenberg, a pediatrician at Yale. “I’ve had to tell families that this one child is eligible and this one child is not. And that mixes something wonderful and something heartbreaking and difficult.”

Advocates worry that the wrong precedent is being set. Luis Luna, coalition manager of HUSKY 4 Immigrants, said their goal is for everyone to have access to healthcare, no matter their age. He worries about older immigrants, including his 67-year-old father who recently suffered a heart attack. “If we continue on this path of just doing a couple of years every session, my dad will be 90 or so years of age before we get to his age,” Luna said. “We cannot set that precedent.”

According to state Representative Jillian Gilchrest, one of the legislators pushing for expansion, opponents typically fall into two categories: those with funding concerns and those with anti-immigrant sentiments.

As far as funding, some of her colleagues would prefer to gradually expand the age limit, so as to better understand and predict the fiscal impact. Gilchrest said it is difficult to guess the cost of expansion because the state lacks an accurate count of its undocumented immigrants. In his testimony last February, the director of Connecticut Medicaid, Gui Woolston, testified against the proposed bill and wrote that “the Department has not yet had a chance to evaluate the effectiveness of the program or its actual cost to the state.”

However, advocates for expansion argue that expanding HUSKY would benefit the state in the long run.

They cite a study by the RAND corporation estimating that Connecticut’s hospitals would save 63.3 million dollars if all undocumented immigrants were eligible for HUSKY, while the actual cost to the state would equal 3 percent of the state’s 3 billion dollar budget for Medicaid.

Susan Levine, a physician and director of University of Connecticut’s Immigrant Health program, noted that the state’s only public hospital, UConn John Dempsey Hospital, already writes off millions each year in charity care for undocumented patients. The state also has an emergency Medicaid program through which undocumented immigrants receive urgent care; in 2021, this program cost the state around $15 million. “By not affording people healthcare in our state, we’re just going to be taking on the costs later on,” Gilchrest said.

Dr. Levine offered an example: If a chronic disease such as diabetes is caught early, it can be controlled. But if the diabetes is left untreated, this could lead to a complication called diabetic ketoacidosis, sending the patient to the emergency room with a bill upwards of 60 thousand dollars. That stay could be written off as charity care—and the patient would be discharged without access to the proper medications, continuing a vicious cycle of repeat admissions that may end in a stroke, heart attack, or other disabling complications.

To Levine, investing in preventive care would enable less costly health outcomes over a lifetime. That means more stable families, better workforce participation, and improved school attendance. “To deny those people medical coverage is really, I think, shortsighted,” she said.

Some opponents of expansion are against supporting undocumented immigrants altogether, Gilchrest said. It’s been easier to convince these colleagues to cover children first. “If you’re discriminatory against undocumented immigrants, you might not be as discriminatory against children. ‘They didn’t choose to come here’ is what I hear often,” she added.

To state Senator Saud Anwar, another politician fighting for HUSKY expansion, those who discriminate against undocumented immigrants fail to recognize the significant delays and weaknesses plaguing the legal immigration process. “For generations, everybody has been an immigrant, and it’s almost unfortunate that there is a little bit of forgetfulness on that part,” said Anwar, who is an immigrant from Pakistan.

As a physician himself, he emphasized the need to invest in the health of younger generations, whether they were born here or immigrated from abroad. “[Consider] our economic needs, our manufacturing needs, our healthcare needs, our needs for people to pay more taxes, for sustainability of the society, our need to fill our universities with the smartest people and our needs to have people in all walks of life,” Anwar said.

Gilchrest is hopeful that bias against undocumented immigrants will lessen as HUSKY coverage rolls out. She noted that Connecticut is a progressive state, and was at the forefront of offering in-state tuition and financial aid to undocumented immigrants.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In future legislative sessions, Gilchrest hopes to expand HUSKY eligibility to age 26, but her backup plan is to push for age 18. The state recently launched studies to evaluate the feasibility of these potential expansions using data from the most recent increase. Gilchrest said the results will come out in time for the 2025 legislative session.

As for this year’s legislative session, another raise would be unlikely. “I think politically it would be hard this year to push for an increase when we don’t yet have that information from the study,” she explained. Anwar agreed: Another issue is that the budget is set every two years, and the most recent already allotted funds for fiscal years 2024 to 2025.

While the state is not moving as fast as she would like, Gilchrest believes they will get there eventually. “I’d love to see us cover all undocumented individuals in the state of Connecticut.”

Luna said his coalition is meeting regularly with the Department of Social Services to provide feedback as they roll out the program. And though a new bill will not be introduced this session, the coalition is still hoping to expand eligibility to age 18 by pressuring the appropriations committee to allocate funds toward it, according to Anjali Mangla, who chairs the HUSKY 4 Immigrants Coalition’s communications committee.

Another group, the Semilla Collective of New Haven, is tackling language barriers in the application process by accompanying members to visits and calls with DSS, said one member, Javier Villatoro.

As a 27-year-old undocumented immigrant, Villatoro often has to choose between paying his rent and going to the doctor. “My teeth are hurting and I’m literally holding back the pain. I gotta choose between going to check that up or getting myself dinner for the next week,” he said. “We neglect ourselves.” As an advocate, he hopes others won’t have to suffer the same.

“I’m not doing it for me. I don’t think I’m gonna get the fruits of this campaign in my lifetime,” Villatoro added. “I’m doing it for the people who come after me.”

Najely Clavijo, an organizer for CT Students for a Dream, has a similar mindset. She’s happy for her brother Darek and all the other children who will benefit from HUSKY. She also hopes, one day, to be next. “Healthcare should be a human right regardless of age, and especially immigration status,” she said. “Because people don’t stop getting sick after 15.”

Thank you for reading The Nation!

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read, just one of the many incisive, deeply-reported articles we publish daily. Now more than ever, we need fearless journalism that shifts the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media.

Throughout this critical election year and a time of media austerity and renewed campus activism and rising labor organizing, independent journalism that gets to the heart of the matter is more critical than ever before. Donate right now and help us hold the powerful accountable, shine a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug, and build a more just and equitable future.

For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and moral clarity. As a reader-supported publication, we are not beholden to the whims of advertisers or a corporate owner. But it does take financial resources to report on stories that may take weeks or months to properly investigate, thoroughly edit and fact-check articles, and get our stories into the hands of readers.

Donate today and stand with us for a better future. Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.

Thank you for your generosity.

More from The Nation

MTA Bus Drivers Don’t Work for the Cops MTA Bus Drivers Don’t Work for the Cops

The six bus drivers who walked off the job rather than transport protesters slowed the city’s mass-arrest machine by sticking to their union-negotiated contract.

The Abolitionist Roots of Anti-War Encampments The Abolitionist Roots of Anti-War Encampments

From Minneapolis to Manhattan, the encampments now spreading across college campuses are built on the same principles as abolitionist spaces like George Floyd Square.

Students at Brown Just Secured a Vote on Divestment. What Happens Next? Students at Brown Just Secured a Vote on Divestment. What Happens Next?

On April 30, protesters disbanded their encampment when the university pledged to vote on divestment from companies affiliated with Israel. This shows a different way of doing thi...

This Is How Power Protects Itself This Is How Power Protects Itself

The decision to sic the police on peaceful protesters is evidence that people in charge are panicking. They’re terrified of the strength of the movement for Palestine.