Kazuo Inamori, Kyocera founder and part-time San Diegan who created Kyoto Prize, dies at 90

Ceramics tycoon considered city a home away from home

Kazuo Inamori, a Japanese tycoon and founder of the international Kyoto Prize, whose laureates are honored annually in San Diego, died Aug. 24 at home in Kyoto, Japan. He was 90.

His death from natural causes was announced by Kyocera, the ceramics and electronics company he founded in 1959. Its North American headquarters are in San Diego, a city that Inamori — who owned a condo downtown — thought of as a home away from home.

Widely considered one of the leaders of Japan’s post-World War II industrial boom, Inamori mixed a fierce work ethic — sleeping in a factory at times early on — with a belief that divine intervention made success possible.

“If one works very hard in a certain area, struggling day after day after day continuously, then it so happens that such a person may experience some kind of a serendipity, if you will,” he told the Union-Tribune in a 2013 interview.

“I have personally experienced that and reached a breakthrough after a long and hard struggle. I felt as if God gave me a hint. Somewhere in this universe there is a treasure house of wisdom where this kind of awakening or serendipity is provided.”

Born Jan. 30, 1932, in Kagoshima, Inamori was diagnosed with tuberculosis when he was 13. He thought he might die from the disease, which had already killed two of his uncles. While he was bedridden, a neighbor gave him books by Masaharu Taniguchi, a spiritual thinker, which Inamori devoured. He later credited them with prompting him to focus on life’s journey, not its final destination.

After college, he worked for a small manufacturer in Kyoto, making ceramic parts for TV sets and other electronics. Unhappy with the direction of the company, he left in 1959 and was joined by seven colleagues. They started Kyoto Ceramics, now known as Kyocera.

Its North American headquarters opened in San Diego in 1971 to manufacture semiconductors, the first Japanese-owned company with production operations in California..

In addition to Kyocera, which was launched with the equivalent of $10,000, Inamori created a long-distance phone carrier in 1984 that challenged what had been a government monopoly. It grew into KDDI, one of Japan’s leading telecommunications companies.

He retired in 1997 and became a Buddhist priest, shaving his head and immersing himself more deeply into a life of reflection and altruism. At the request of the Japanese government, he returned to the business world in 2010 to rebuild Japan Airlines as it emerged from bankruptcy.

By then, he had amassed a fortune and was giving parts of it away through the Inamori Foundation, established in 1984. One of its major projects, first presented a year later, is the Kyoto Prize.

He identified three areas that were not covered by the Nobel prizes: advanced technology, basic sciences, and arts and philosophy.

“We would like to believe that our endeavors are contributing to building a brighter future for humankind,” Inamori said when he discussed the prizes with the Union-Tribune in a 2004 interview.

Past winners have included primate researcher Jane Goodall, pop art painter Roy Lichtenstein and linguist Noam Chomsky.

Laureates receive a gold medallion, a diploma and 100 million yen (about $750,000). They are honored at a ceremony in Kyoto every year.

In 2002, hoping to raise the profile of the prize, Inamori made a deal with the University of San Diego to have the winners appear on campus and give public lectures. Now known as the Kyoto Prize Symposium, it is a three-day affair that includes a gala, the lectures, and scholarships for local high school students.

The next one is scheduled for March 2023.

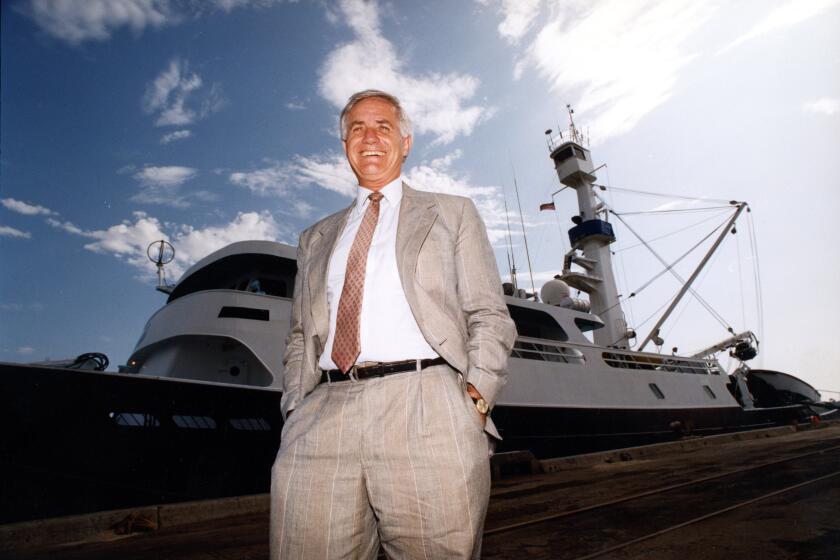

Poor attendance in the first few years almost caused Inamori to move the symposium elsewhere, but a group of San Diegans, including restaurateur Tom Fat and businessman and philanthropist Malin Burnham, flew to Japan and convinced him to keep it here.

“I love San Diego very much,” he told the Union-Tribune after the deal was struck.

Survivors include his wife, Asako, and three daughters. Private memorial services for family have been held. Kyocera said a company memorial service is being planned.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.