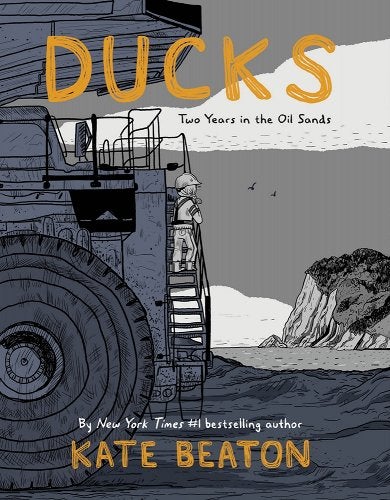

Kate Beaton made her name as the creator of Hark! A Vagrant, a series of whimsical, funny online comics highlighting historical silliness, literary critique, and strong female characters. Her two Hark! collections were both bestsellers. But many fans didn’t know that at the time Beaton posted her first comics about Jane Austen and Marcel Duchamp to Livejournal, she was working in a place that felt like the moon: the oil sands of Alberta. Now Beaton is exploring those two years spent working off her student loan debt in Canada’s mining center in Ducks, a comics memoir that blends her trademark wry humor with sharp social critique and raw personal experience. I talked to Beaton about leaving Cape Breton, looking back on her younger self, and feeling like the only young woman in a hundred-mile radius. This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Slate: There’s a gag early in the book where you introduce yourself in 2005, and then you say, “Well, I’m older now and also I’m three-dimensional.”

Kate Beaton: Yeah.

What was it like writing about and drawing your younger self?

Well, I have been drawing myself since I was that age. My cartoon self hasn’t changed that much. I just draw more bags under my eyes now.

And to revisit a younger version of you?

I really had to separate myself from that person. I had to refer to her as a different person, as Katie, to remove myself as the author so I could look at it as its own story. I had to be very far away from those events in order to make the book in the first place. It took a long time to get, maybe, the skills as a storyteller, as a comic artist. And then I think maybe in some ways the courage and everything to make it. It was very raw in a lot of places. And even though I really wanted to tell it, I also had to sort of be very removed and cold about it, because otherwise I would never be able to get it right, I think.

I also find when writing about my younger self, it’s hard for me not to judge my younger self harshly for the decisions that I made or the things that I said.

I’ve been living with those decisions for a long time. That kind of judgment on myself, or even for a lot of other people in the book, wasn’t really the point.

You write that it’s important for readers to understand two things about Cape Breton, where you’re from. That people who are from there love it, and that people understand that they’re going to have to go somewhere else to make money. Why?

That was especially true when I was growing up. So say in my parents’ class, when they graduated from the school that I went to, there were 90 people in their graduating class. In my graduating class, there were 23. And when I was in grade 12, there were seven kids in grade primary. It was very apparent that you had to go. And this had been bred into people for many generations. I watched my mother’s family come here in the summertime from their jobs in car factories in Windsor and cry on the way back. And I knew that would be me someday, probably.

And why do people love it there?

Because it’s, well, it’s home. I’m talking about settlers, of course. I’m not talking about indigenous people. This is unceded Mi’kmaq territory. But settler populations have been here for a few hundred years. Their cultural memory goes back a long way. But for Atlantic Canada as a whole, the sort of rapid de-industrialization that has been happening here for a long time has led to a sense of loss, I think, that is deeply felt among people since a long time. Because nobody chooses to lose everything. For the ground to like be pulled out from under your feet. And to be a have-not province in the country. And the money to be elsewhere. And have to say, “Well, I’ll go and I’ll make the money, but maybe I’ll come home after I make the money.” And then you go, and then your life is somewhere else. And you keep saying, “Well, maybe I’ll come back after I make the money.” But then you’ve got your family somewhere else. And then you’ve got your grandkids there. Your whole life, you say, “Oh, maybe I’ll come home. I’ll come home.” And you never fucking come home.

I’m sorry. I curse a lot.

That’s fine!

You know what, that is a result from being in Fort McMurray, because everyone cursed their faces off and I picked it up. And I haven’t stopped yet.

Fort McMurray is in Alberta, where you spent two years working in the oil sands. Give me just a quick rundown of the actual jobs that you did there.

I started off in the tool crib there, which is like, it’s like the warehouse for tools, pretty much. Signing out tools from the warehouse to the workers, signing them back in, doing inventory, making sure that you’re well stocked and ordering tools, trying to make sure that people don’t steal them, but they did. They totally did. And getting in trouble when they did. You couldn’t help it. It’d be like, “Don’t let them steal the drills.” And then they would come in and you’d say, “Where’s the drill you’re supposed to bring back?” And he’d be like, “Oh someone broke into my toolbox and took it.” But he took it. He took it home. And then you’d have to sign them out another one anyway, because they needed it to do the work. And then I worked my way into the office for small tools, which was like actually ordering supplies and stuff.

Procurement as opposed to distribution.

Yeah.

Within the industry and this region, there are very different kinds of environments. You started out at Syncrude.

That’s a mine, like an open pit sort of mine.

But then you moved to a more remote camp run by a different company.

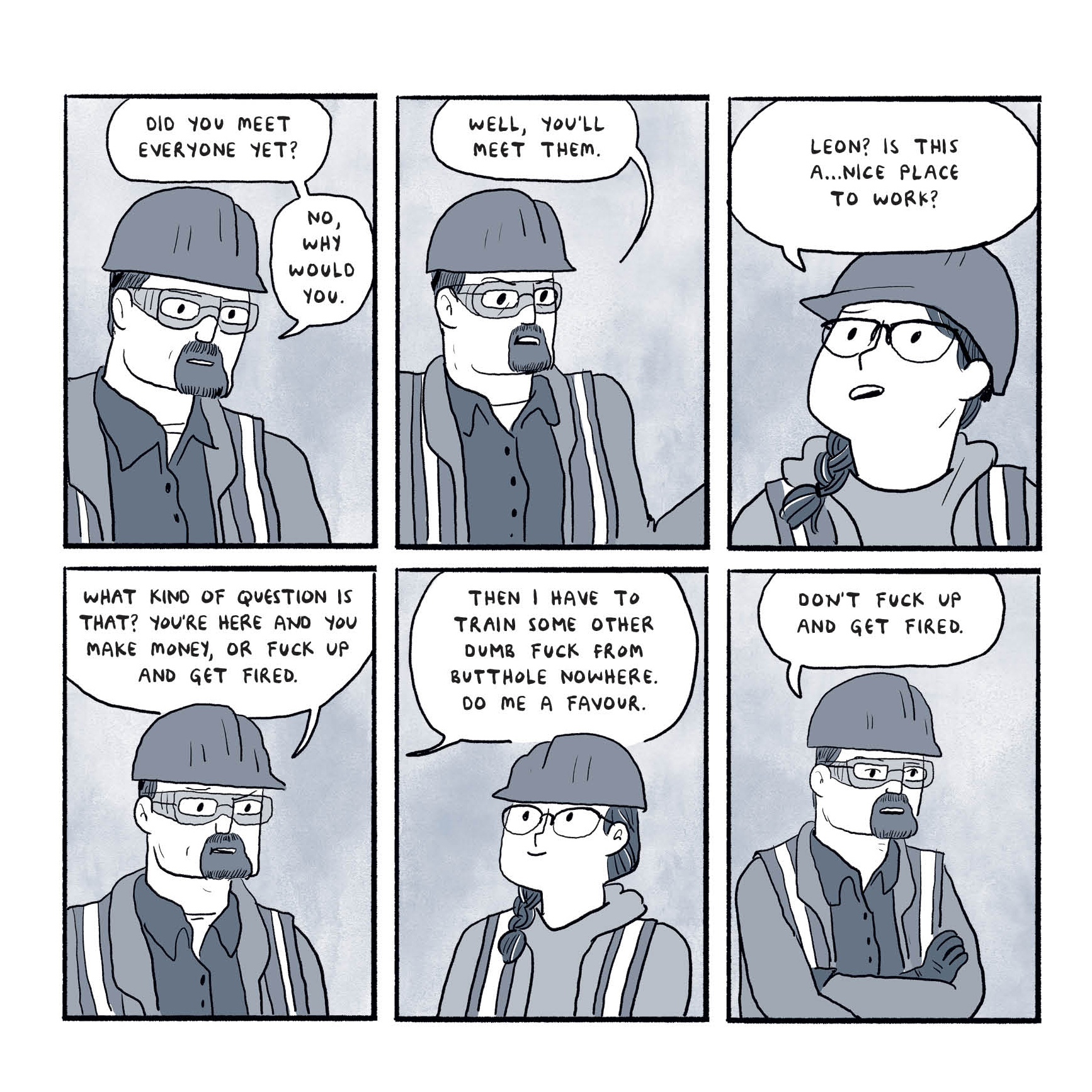

It was not a nice camp. Not all camps are the same. There’s definitely a huge variation in what you get. Everybody will say, like, this camp is nice, this camp is not nice. Some camps are dry. That’s a non-alcoholic camp. Some camps are not. You can tell from the book that Long Lake was not a nice camp, I think.

And then I worked for Shell at Albian Sands. And that was a nicer camp, and we were blown away. We were like, “Wow, this place has a Tim Horton’s. This place has fake plants and, like, a carpet on the floor.” We were like, “Holy shit, wow.” And it had steak night and all the guys were like [guy voice] “Wow, steak night.”

You struggle with the ways that the place you’re working seems to turn people into the worst versions of themselves, even people from Cape Breton. There’s drug abuse and cruelty and harassment. And at one point you ask someone, “Is this who people really are, or are they who they are at home?” What do you think about that now, 20 years later?

It’s very hard to answer that question. Because like, when you think about the lowest time in your life, have you been like, Is this who I really am? I would hope not. And when there are no supports around to help people navigate the stress of that situation, then … Especially when we’re not prepared for it at all. I, for instance, I had no idea what I was getting into. And I didn’t know how to handle it. I didn’t know how to … I didn’t know that I would be slammed with that kind of loneliness. Or the sexual harassment.

And for men going out there, there was nothing. There was nothing to help them with the loneliness or the pressure with having to make big money or to perform in that hyper-masculine environment where everyone is trying to sort of one-up one another. And you could only take so much of that before, like, it starts to come out through whatever channel it goes out of. Unfortunately, that energy piles up on top of me, because I’m like an easy channel for it.

I’m not saying that I excuse bad behavior that was hurled my way. But I do see the sort of equation that made that happen. So is that who they really are? I don’t know. It might be who some of them are. But I also think that it turns people into that.

There’s a real conflict in the story between you trying to wrestle with this question and the loyalty that you still feel, particularly to the people who come from where you are from. There’s a scene where a reporter in Toronto wants to interview you about what it’s like being a young woman in the oil sands.

Yeah.

And you don’t want to open up to her. And I was really struck by what you said there: that they’re still your people, even at their worst.

I found that not just her, but like a lot of people, when they found out that I worked in the oil sands, they immediately went into: “How gross were they?” “What did they say to you?”

“What’s the worst thing anyone ever said to you?”

Yeah, they wanted the tea. And it was tough because you don’t want to be a position of defending people who were really shitty to you a lot of the time. So you’ve got to try to explain how this place resocializes people to be shitty to you. So when people lean in and they’re like, “How terrible was it? Like, was it like a gulag of assholes?” And no, that’s not the way the human race works. It only takes a couple of people to make you kind of miserable. And that’s enough. That’s plenty.

You started posting Hark! A Vagrant online while you were working in the oil sands. Do you remember feeling a real cognitive dissonance between the art you were making and the life you were living?

Totally. Because like, I was posting things on LiveJournal, and there was a community of artists who would talk to me like I was myself online. And that made me feel so good. That made me feel so validated. They were talking to me. Me, the person. And then I walked outside of my office and people were barking at me like a dog.

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands

By Kate Beaton. Drawn & Quarterly.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

Have you found that your experience in the tool crib is useful to you now? Can you identify an impact adapter on sight?

I’ve married someone who grew up on a farm and he’s way handier than I am. So I find myself paling in comparison. Sometimes I’m like, “Ooh, I know what this is.” But it’s very much a parlor trick. Because I never used the tools, I just signed them out. It’s not so good if you’re just like, “Oh, a grinder!” and then, asked to grind, you’re like, “Hmm, I don’t know.”