Newsletter Signup

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com

Earlier this year, Massachusetts introduced its most-expensive scratch ticket ever: a $50 ticket dubbed “Billion Dollar Extravaganza.” After declining sales in the latter half of 2022, the new ticket has been a boon for the Lottery, helping it break sales records.

Massachusetts has the highest per capita lottery sales in the country. Proponents of the new ticket, and of the lottery in general, are espousing the benefits of this revenue and the money it will create for Massachusetts communities. Opponents are arguing that the $50 ticket is just the latest cog in a machine that disproportionately impacts low-income residents.

The debate begs the question: how did we get here? New England was the home of the country’s first legal lottery and a hotbed for lottery innovation and experimentation. Over the decades these systems grew and multiplied, evolving into the well-oiled machines that run throughout nearly the entire country today.

On April 30, 1963, New Hampshire became the first state to have a legal, government-operated lottery. It was the culmination of about a decade’s worth of work for people like State Rep. Larry Pickett of Keene, who spearheaded the effort and proposed five different “sweepstakes” bills before getting one to pass. Residents were fiercely divided over the idea, and Gov. John King reportedly spent two weeks alone in his office deciding if he would veto the bill or not.

Illegal lotteries and numbers games had been in operation throughout the country. By the 60s, postwar economic mobility appeared to have diminished and states needed new revenue sources. Conditions were primed for a state to take the plunge into a government-sanctioned lottery. New Hampshire, as one of three states at the time without sales or income tax, felt the squeeze, according to Jonathan D. Cohen, a historian and the author of “For a Dollar and a Dream: State Lotteries in Modern America.”

Crucially, Cohen said, the concept of a government-run lottery could be sold to voters as a way to improve schools and other services without increasing taxes.

“The way that the lottery was sold to the public had this element of gambling, of course, you’re going to be able to play, to gamble. But a lot of it was, ‘We are going to be raising money for schools,’” Cohen said. “People were not modest with their expectations, with their projections for the type of money that a lottery would bring in. It really was seen in this early wave, not just in New Hampshire but in other states too, as a panacea.”

The New Hampshire lottery introduced in 1963 was quite different from today’s system. Winning ticket holders were matched up with a racehorse. If that player’s horse won a specified race, they would receive a jackpot.

Although New Hampshire’s inaugural lottery drew no shortage of controversy, one thing was clear: public interest was high.

That public interest, of course, was not limited to the residents of New Hampshire. People from all over flocked to the Granite State for a piece of the action, Cohen said, and the winds of change were blowing fiercely. Massachusetts lawmakers saw that residents were traveling to play the New Hampshire sweepstakes, and a sentiment grew over the following years that, if residents were playing anyway, it made sense to keep those dollars in-state.

This, Cohen said, is how lotteries spread from 1963 through 1977: as a sort of contagion where proximity to another legal lottery made it more likely that a state would create one of its own.

“That’s how we get this sort of domino theory, where it just feels inevitable. This is what’s happening right now with sports gambling and what’s happening right now with marijuana legalization,” he said.

Another factor working to help lotteries spread in New England was religion. When studying the spread of lotteries during this first wave, researchers have found that there was a direct correlation between the percentage of a state’s population that was Catholic and the odds that it adopted a lottery. It’s very clear, Cohen said, that the larger the share of Catholic voters in a state during this time, the more likely it was to adopt a lottery.

Not everyone was on board then, or today.

“The lottery opponents in New Hampshire in 1963 look really similar to the lottery opponents in Massachusetts in 1970 to Mississippi in 2018,” Cohen said.

Typically, he added, lottery opponents break down into three groups: evangelical protestants, social-justice-minded liberals, and representatives from other gambling industries who feel threatened by a new competitor. Concerns generally included a lottery’s impact on low-income residents, its perceived undermining of a traditional work ethic, and that it could become a front for criminal organizations.

“In almost every case, these concerns were not enough to match up with gambling fever: the desire of people not just to have the chance to bet, but to have the chance for tax-free revenue,” Cohen said.

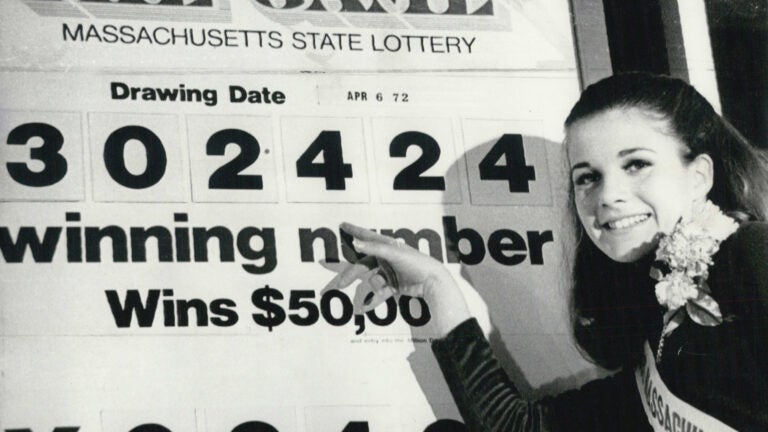

In the ’70s, legal lotteries started to resemble the games millions of people play today. Massachusetts officials were at the forefront of many of these changes. In 1974, the Bay State introduced the industry’s first instant scratch ticket. It was a way to give players an immediate result, compared to the slower-paced drawings of the previous decade.

These scratch tickets, which cost $1 at the time, were still slow compared to their modern counterparts. Players did not instantly win major jackpots after scratching their tickets. Instead, winners were generally invited to an in-person drawing that was sometimes televised. All the finalists were guaranteed smaller prizes, but one got a large jackpot after attending a final drawing.

The next major development came four years later.

“The ’70s were a period of experimentation for lottery commissions, and Massachusetts, to their credit, was the most willing to be the most experimental with adopting scratch tickets in 1974 and then lotto in 1978,” Cohen said.

Massachusetts became the first state in the country to introduce a lotto game, where the jackpot gets progressively larger based on the number of tickets sold. Today’s multi-state Powerball and Mega Millions games are prime examples of lotto games, which are believed to date back to 14th-century Italy.

But, unlike instant scratch tickets, the lotto game introduced in Massachusetts was simply not successful. The jackpot was perceived as being too small and accumulating too slowly, Cohen said. People reasoned that they might as well play weekly games with better odds. It was pulled after just 13 weeks.

Around this time, a lotto game was also created in New York, where it did succeed. Lottery officials there understood that the game took more patience, and that it was cyclical by nature, Cohen said. As the lotto jackpot gets bigger, more people start playing. As more people start playing, the jackpot increases. New York officials understood that the goal was to create a large jackpot, and the rest would follow.

The emphasis on jackpot sizes has continued into the present day. Over the years, Powerball and Mega Millions made jackpots harder and harder to win, Cohen said. Officials reason that players have a hard time caring about, or telling the difference between games with different odds of winning. But, Cohen added, they can definitely tell the difference between a $4 million jackpot and a $400 million jackpot. The odds of winning already feel so distant, so improbable, that one might as well compete for the largest jackpot.

Scratch tickets, since their introduction in Massachusetts, have been designed in a way to keep people hopeful and interested in an addictive, logic-defying way. Tickets are often designed so that losing numbers are numerically closer to winning numbers, giving players the feeling of “Oh, I was just one off,” Cohen said. Numbers on scratch tickets are also formatted so they resemble other numbers until a player finishes scratching to reveal the entire number. The idea is to give players a fleeting feeling of winning that can be chased by buying another ticket, Cohen added.

The future of lotteries will likely rely on the distant odds and massive prizes that set the games apart from other types of gambling, Cohen said. This translates to more expensive scratch tickets, such as the $50 offering in Massachusetts and a $100 ticket introduced in Texas last year.

When the economy takes a downturn, when unemployment rates rise, spending decreases on most gambling, Cohen said. This is not the case with lotteries, as sales generally increase when economic turmoil strikes.

What sets playing the lottery apart from other forms of gambling is the potential for a massive windfall that is totally out of proportion to the amount of money bet.

“Of all the other types of gambling, whether it’s sports betting or something else, the lottery is the only one where you can come in with $2 and leave with $2 billion,” Cohen said. “The enduring popularity of lotteries tells me that a lot of Americans see it as their last, best, or only chance at a new life.”

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com

Stay up to date with everything Boston. Receive the latest news and breaking updates, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.

Conversation

This discussion has ended. Please join elsewhere on Boston.com