Hate speech is one of the most reliable predictors of violence in any community. Researchers have worked for years to develop methods to track its prevalence in conflict-prone areas. It can act as an early-warning system to predict impending incidents of brutality. Now scientists are trying to see if they can do something similar for hate speech’s opposite—they want to measure what they call “peace speech” as well.

In a new paper published in PLOS ONE, a group of researchers used an algorithm to characterize and quantify peace speech in different countries’ media. They believe their result—the ability to identify words and phrases circulating in the media during times when violence is absent versus prevalent—could help predict when a nation is becoming more or less hostile. Detecting these subtle changes in the language that pops up in endless news streams could even help promote civic harmony in unstable times. “Peace isn’t just the absence of conflict,” says Larry Liebovitch, an adjunct senior research scholar at Columbia University, who co-authored the study. “Societies do very conscious things to help generate and support [it].”

To detect the prevalence of peace talk, Liebovitch and his team trained a machine-learning model on more than 700,000 English-language news articles from 18 different countries, which were categorized on a spectrum ranging from high- to low-peace. The researchers used several indices, including the Global Peace Index and the World Happiness Index, to determine where on this spectrum each nation belonged. After adjusting for ubiquitous parts of speech such as “the,” “a” or “an,” they queried the algorithm to identify the most common words used in media from the six most peaceful and four most conflict-ridden countries.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Initially Liebovitch expected that articles discovered in higher-peace regions would use more words such as “harmony” or “moderation,” while dispatches from tumultuous places would use “conflict,” “strife,” and so on. But the results surprised him. “It was more subtle than that,” he says.

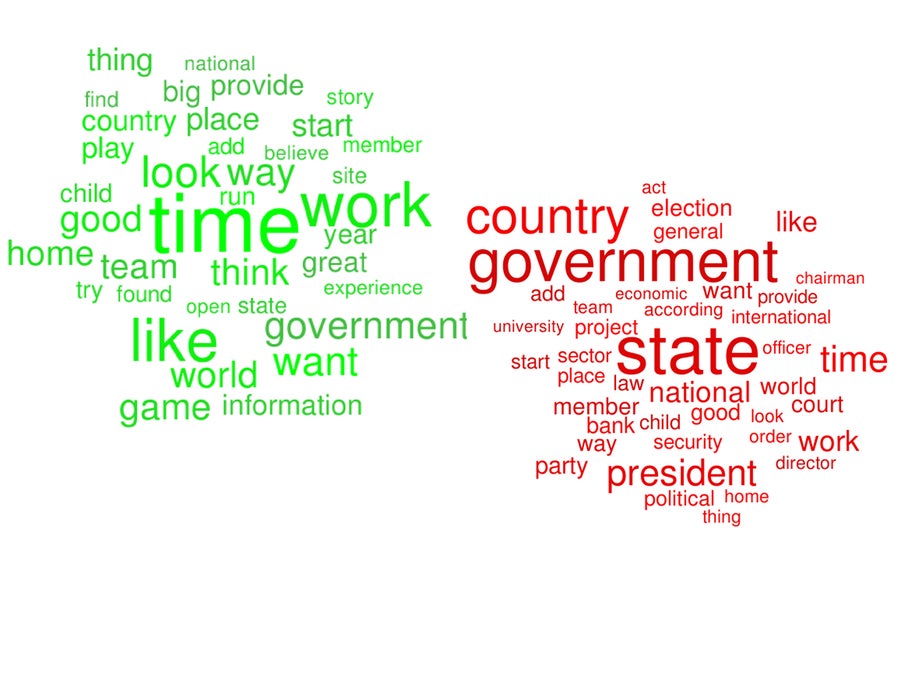

Based on their model, the researchers found that articles from peaceful countries tended to focus on the activities of daily life and planning for the future. Words such as “home,” “play” and “experience” were common. In less peaceful nations, however, the media used significantly more words related to government authority and control—typified by the likes of “state” or “security.”

Words in news media more associated with more peaceful countries (left) and words in news media more associated with less peaceful countries (right). Source: “Word Differences in News Media of Lower and Higher Peace Countries Revealed by Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning,” by Larry S. Liebovitch et al., in PLOS ONE, Vol 18, No. 11; November 1, 2023 (CC-BY 4.0)

While machine-learning models have been used in hate speech research before, this is among the first studies using them to characterize peace talk. “The authors are adopting a very interesting and novel approach,” says Linda Tropp, a social psychologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who was not involved in the study.

But she points out that even when using an algorithm and controlling for prepositional phrases and the like, significant overlap occurs between the lists of most frequently used words in high-peace and low-peace countries. “A word like ‘good’ actually appears on both,” she says. This could skew the model’s assessment of nations that don’t clearly fall onto one side of the spectrum or the other.

And while the model may be able to capture the contrasting peaceful or hostile attitudes exhibited by a country’s government, those may not represent the views of the majority of its citizens, Tropp says. This is especially true for nations with authoritarian leaders, which might have news outlets that are monitored or controlled by the government. But using algorithms to track certain words in a country’s media might still prove a useful indicator of whether that nation’s leadership is becoming more or less hawkish over time.

Looking ahead, Liebovitch and his colleagues plan to train similar models in languages other than English. They also hope to create a dashboard of words that indicate a trend toward more harmonious societies.

Perhaps the most important message from this this type of research has to do with finding a new means for promoting peace. The study highlights an existing feedback loop between newsrooms, governments and the general public. “Ultimately some of the results of this may help inform journalists on how they report things,” Liebovitch says. It is critically important to take care in choosing one’s words because their meaning can add fuel to a raging fire or help douse rhetorical flames.