Ancient Egyptians May Have Corralled Millions of Wild Birds to Sacrifice and Turn into Mummies

New DNA evidence suggests that Egyptians captured wild birds for millions of ritualistic sacrifices, rather than farming the animals.

Ancient Egyptians captured and temporarily tamed wild birds by the millions in order to mummify the animals in ritualistic sacrifices, new research suggests.

Egyptian catacombs contain troves of mummified birds, specifically African sacred ibises, stacked atop each other in tiny jars and coffins. But how did the ancient people collect all those birds to begin with? Given the sheer number of avian mummies, scholars have long theorized that Egyptians must have farmed ibises to meet demand. But when a team of geneticists took a closer look, they determined that Egyptians probably plucked wild ibises from their natural habitats.

The research, published Nov. 13 in PLOS One, drew DNA samples from 40 mummified ibises excavated from six different Egyptian catacombs. The mummies were interred around 2,500 years ago (about 481 B.C.), the researchers reported in their paper. That means the birds met their fate when ibis sacrifice was common practice in Egypt, between about 650 B.C. and 250 B.C. From 14 of the ancient birds, the researchers obtained complete genomes from the animals' mitochondria, the tiny powerhouses that generate energy for each cell and contain their own special DNA. The authors compared this ancient genetic material to that of 26 modern African sacred ibises to see which set appeared more genetically diverse, which could reveal clues about the ancient birds' origin.

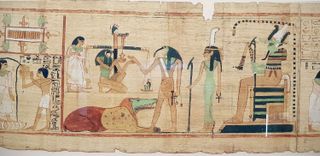

Related: In Photos: Ancient Egyptian Tombs Decorated with Creatures

If Egyptians had raised the ancient ibises on farms, inbreeding among the birds would have caused the animals' DNA to look more and more similar through time, the authors noted. But the DNA analysis instead revealed that the ancient and modern birds showed similar genetic diversity.

"The genetic variations did not indicate any pattern of long-term farming similar to chicken farms nowadays," co-author Sally Wasef, a paleogeneticist at Griffith University in Australia, told National Geographic. Wasef and her colleagues suggested that priests likely corralled the wild birds in local wetlands or temporary farms and then tended to the animals for a short time just before their sacrifice.

But not all Egypt experts agree.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We are still talking millions of animals at different sites all over Egypt, so relying just on the hunting of wild ones does not convince me," Francisco Bosch-Puche, an archaeologist at the University of Oxford, told National Geographic.

Bosch-Puche compared ancient Egypt to a bird mummy-making "factory," an industrial force that could not possibly be sustained by wild birds alone. Additionally, some ibis mummies show evidence of having recovered from illnesses or injuries that would have doomed a wild bird to starvation or death at the hands of a predator. Bosch-Puche suggested that some wild ibises may have wandered onto farms in search of food, thus diversifying the captive populations.

- 7 Amazing Archaeological Discoveries from Egypt

- Genetics by the Numbers: 10 Tantalizing Tales

- 7 Bizarre Ancient Cultures That History Forgot

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Most Popular