A NASA spacecraft has begun its journey to a realm of the outer Solar System that has never before been visited: a set of asteroids orbiting the Sun near Jupiter. The rocks are “the last unexplored but relatively accessible population of small bodies” circling the Sun, says Vishnu Reddy, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

The US$981-million Lucy mission lifted off from Cape Canaveral, Florida on 16 October, and will spend the next 12 years performing gravitational gymnastics to swoop past six of the asteroids, known as Trojans, to snap photos and determine their compositions. Scientists think the Trojans will reveal information about the formation and evolution of the Solar System. The mission’s name reflects their hopes: Lucy is the 3.2-million-year-old hominid fossil unearthed in 1974 in Ethiopia that unlocked secrets of human origins.

The Trojans “are very mysterious, which makes them really fun”, says Audrey Martin, a planetary scientist at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, who works with the Lucy mission.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The asteroids probably formed in the outermost reaches of the Solar System around 4.6 billion years ago, when Earth, Jupiter and other planets were coalescing from a disk of gas and dust around the newborn Sun. In this scenario, gravitational interactions would have slung the Trojans inwards, where they now orbit as relatively pristine examples of the Solar System's building blocks.

Scientists can study the Trojans to understand what the distant, primordial parts of the Solar System are like, without having to send a mission all the way out there.

From the outer reaches

Since 1991, when the Galileo spacecraft whizzed past the asteroid Gaspra on its way to Jupiter, a number of missions have explored the Solar System’s main asteroid belt, which lies between Mars and Jupiter. But no mission has ever gone to Jupiter’s Trojans, which might be very different from asteroids in the main belt. “Every time we go to new populations, we learn new things,” says Cathy Olkin, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, and Lucy’s deputy principal investigator.

More than 7,000 Trojan asteroids travel near Jupiter, in two large swarms that lead and trail the planet as it orbits the Sun. Several other planets, including Mars and Neptune, also have Trojan asteroids that closely follow their orbits; Earth has at least two. But Jupiter has by far the most known Trojans.

When the Solar System formed, according to a leading model of planetary formation, the planets were much closer to the Sun than they are today. Gravitational interactions then caused many of them to migrate. Saturn, Uranus and Neptune moved outwards from the Sun, while Jupiter moved slightly inwards. In this chaos, icy bodies from the Solar System’s outermost reaches—the Kuiper Belt, where Pluto and other small objects orbit today—got tossed inwards. Jupiter captured them, and they have remained nearby ever since, essentially unaltered for billions of years. That makes them an important part of understanding the origin and evolution of the Solar System, says Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s planetary-science division at the agency’s headquarters in Washington DC.

Rewriting textbooks

Perhaps because of their turbulent origin, the Trojan asteroids—named after characters in Homer’s epic poem the Iliad—have a wide variety of colours, shapes and sizes. Lucy will visit six of them in an effort to determine why they are so diverse. The spacecraft’s targets include Eurybates, a 64-kilometre-wide remnant of a massive cosmic collision, and its tiny moon Queta, discovered last year with the Hubble Space Telescope. Others are the 20-kilometre-long, football-shaped Leucus, and the pair known as Patroclus and Menoetius, which orbit one another and are both around 100 kilometres across. Such binary asteroids are common in the Kuiper Belt, but not, as far as scientists can tell, among Trojans.

After launch, Lucy will make several loops past Earth to gain the gravitational boost needed to head towards its first target, Eurybates, which it won’t reach until 2027. The final flyby, of Patroclus and Menoetius, won’t happen until 2033. “You definitely have to be patient when you’re trying to explore the outer Solar System,” Olkin says.

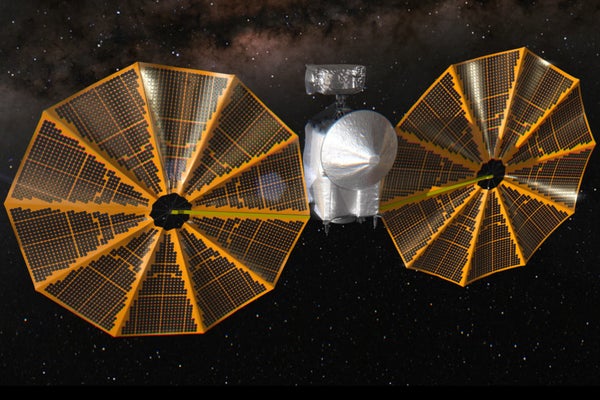

Powered by two 7.3-metre-wide solar panels, Lucy will whiz past each asteroid at 6 to 9 kilometres per second, taking measurements including the asteroid’s colour, composition, spin and mass. Whatever the mission finds will almost certainly rewrite textbook entries on the Trojan asteroids, Reddy says. “We might throw all our formation models out the window.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on October 14 2021.