On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

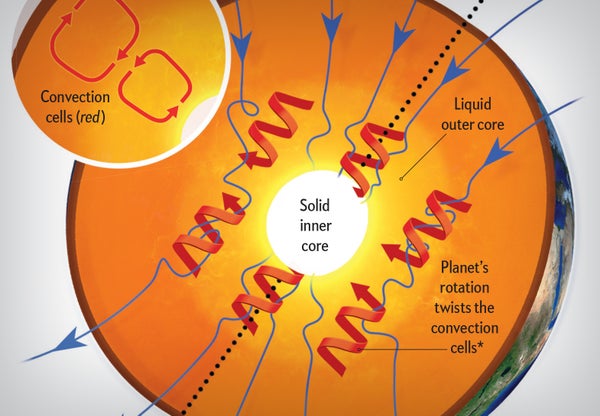

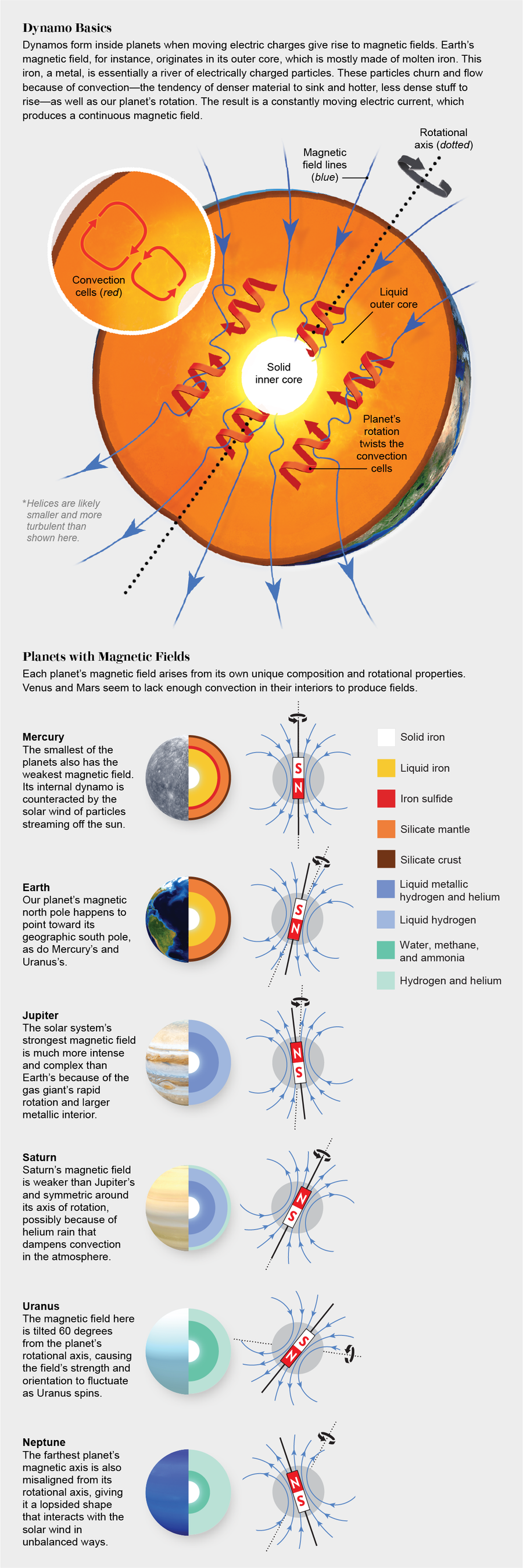

The magnetic fields in our solar system are surprisingly diverse—Jupiter's and Saturn's are extremely strong, but Mercury's is puny. Uranus's and Neptune's are out of whack with the direction of their rotation, although others are closely aligned. And each has a unique set of conditions that gives rise to a dynamo—the engine thought to activate a magnetic field.

Several upcoming space missions seek to study planetary magnetic fields, which offer a window into planets' internal makeup as well as their history and formation. NASA's Juno mission, for instance, is orbiting Jupiter with two sensor experiments to make the first global map of its magnetic field, the strongest in the solar system. And the European Space Agency has a mission in orbit now called Swarm, focused on monitoring how Earth's magnetic field changes over time.

Credit: Mark Belan; Sources: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington (Mercury’s surface); Reto Stöckli, NASA Earth Observatory (Earth’s surface); NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute (Jupiter’s surface)