📚 Stay up-to-date on the Book Club

Catch up on the latest Boston.com Book Club pick and join the virtual author discussions.

After spending time in foster care and then living homeless, I enrolled at Harvard during the peak of the Occupy movement, a time when protesters camped out at picturesque spots around the Yard. Although economic inequality had defined my adolescence, I felt excluded from the conversation; I didn’t even understand the vocabulary. If anything, it seemed that living through the inequities my prep-school peers condemned had rendered me somehow less qualified to speak about them.

I also lacked words to describe this phenomenon until I stumbled on internet personality Rob Henderson’s concept of “luxury beliefs” – “ideas and opinions that confer status on the upper class at little cost, while often inflicting costs on the lower classes” – epitomized by well-heeled denizens of fancy neighborhoods demanding to “defund the police,” slim women touting the virtues of “health at any size” and Ivy League students declaring Goldman Sachs “evil” (a calculated move, according to Henderson, to winnow away competition for Wall Street internships). To Henderson, social justice rhetoric is the new Birkin bag: It’s not meant to lift the vulnerable up; it’s designed to keep them out.

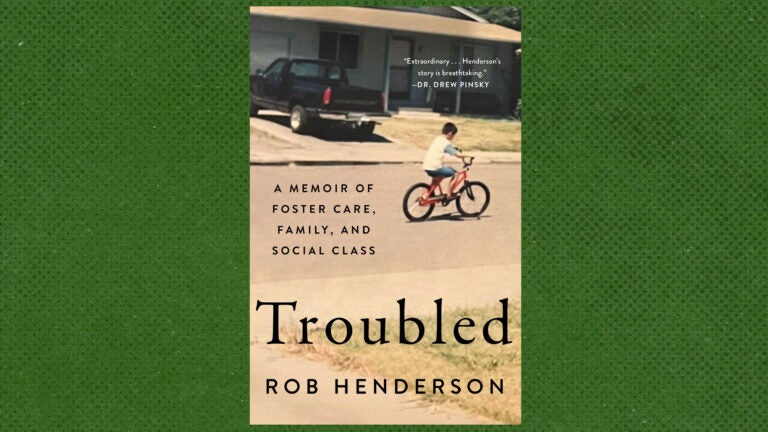

Henderson, known for his viral tweets and conservative Substack newsletter, has now written a memoir, “Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social Class,” connecting his signature idea to his remarkable life, from a childhood in foster care to his time at Yale and Cambridge universities. “Troubled” is being positioned as a new “Hillbilly Elegy,” just in time to explain a second potential Trump presidency. Republican Sen. J.D. Vance (Ohio), author of that earlier bestseller, blurbed Henderson’s book, as did right-wing men’s self-help guru Jordan Peterson. And like many of his predecessors, Henderson sets out to prove that out-of-touch liberal values are destroying the American family and, thus, society.

“Troubled” is a mystifying book about hypocrisy. Meant to skewer elites, it also inadvertently provides insight into contradictions among poor communities and within Henderson himself. While “Troubled” convinces readers that those in power don’t understand the reality of the masses, it falls short by omitting discussions of policy. The idea that luxury beliefs alone have caused this nation’s ills deserves serious skepticism – far beyond what it will encounter on the talk show circuit.

Henderson survived a gut-wrenching childhood. Born to a drug-addicted Korean college dropout and a father he can’t remember, Henderson spent the first year of life living in a car. When he was 3 years old, neighbors called the police after hearing him wail for hours while his mother got high. As a result, Henderson’s mom was arrested and deported. He entered foster care, bouncing through 10 homes over four years until he was adopted by a family in Red Bluff, Calif. That idyll collapsed after a divorce and the subsequent abandonment by his adopted father. His adopted mother formed a stable partnership with another woman, but that bond, too, dissolved after his mom’s girlfriend was accidentally shot and disabled, eventually leading to financial ruin. Although Henderson doesn’t connect the dots, careful readers will note that not all tragedies are results of personal shortcomings; even those that are get magnified by systemic failures.

“Troubled” clearly portrays the negative effects of instability. Henderson started drinking beer at 4 years old and habitually smoking pot at 10. At 12, he was offered crystal meth. (Fortunately, he didn’t care for the stench.) For more than 100 pages, Henderson and his friends get high, drive drunk, pick fights and commit property crimes around their poor, rural town. Teachers try to steer Henderson onto a different path, but he blows them off, explaining, “Even when you present opportunities to deprived kids, many of them will decline them on purpose because, after years of maltreatment they often have little desire to improve their lives.”

After witnessing a drunk friend kick a dog off a cliff, Henderson enlisted in the Air Force, where he began contemplating college. A program for veterans helped him apply and get into Yale. On campus, Henderson was mystified by clueless classmates who enjoyed “The West Wing,” wore expensive Canada Goose parkas and drank water instead of Powerade. Most of these peers were far more liberal and socially permissive than Henderson, championing causes like drug legalization, body positivity and nontraditional family structures. And it is here that Henderson’s concept of luxury beliefs – a new name for an older conservative idea championed most notably by Charles Murray in “Coming Apart” (2012) – began to crystallize. He argues that the ostensible radicalism of his peers was actually hypocrisy born from self-interest: that privileged undergraduates want the less fortunate to be opioid-addicted obese single parents so that they can get ahead and become even wealthier by comparison.

It’s unclear if “Troubled” is intended for fans of inspirational “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” memoirs or readers who turn to nonfiction to understand how larger circumstances shape a life. Ultimately, the book confounds both audiences. Henderson portrays himself as neither hero nor victim, leaving readers with the odd impression of him floating through his youth even as he cites the importance of personal agency. He points out again and again that he is far from exceptional. But then why, one wonders, was his outcome so extraordinary? That question goes unanswered; the implied reasons boil down to chance – a deep irony from a writer who criticizes Ivy League students who cite luck instead of hard work as the reason for their success.

“Troubled” eschews discussions of policy, law, race, economics or history. Instead, Henderson argues that our nation is in turmoil because we glorify learning while failing to acknowledge the primacy of family. Yet Henderson fails to argue that education (along with the economic and social opportunities it confers) and family stability are distinct phenomena in 2024. If anything, his experiences reinforce the deep, if unfortunate, tie between a higher degree and an intact home.

While elite colleges deserve significant criticism for perpetuating inequality and producing out-of-touch leaders, Henderson implies that these institutions are primarily harmful because they foster permissive values and liberal ideas that directly destroy the lives of those less fortunate. Several of Henderson’s examples of luxury beliefs are apt: The movement to defund the police, ostensibly to benefit marginalized people, was most popular among the highest-income Americans and least popular among the lowest.

But his other examples, particularly around family stability, don’t withstand scrutiny. “A student at a top university” told Henderson that within five miles of campus, about half of women on a dating app described themselves as open to multiple simultaneous romantic and sexual relationships; within the broader region, “about half of the women were single mothers.” Henderson draws a causal link between the two. “The poor reap what the luxury belief class sows,” he writes. In some cases, luxury beliefs may yield real, harmful outcomes, but it’s preposterous to suggest that the polyamory of Yalies is causing inner-city kids to grow up in broken homes. More broadly, it’s disrespectful to suggest that ordinary Americans are puppets tugged around by the mores of affluent late adolescents, unable to form judgments or make decisions for themselves.

Readers interested in reforming the foster-care system or creating a better country for children will walk away from “Troubled” frustrated and disappointed. Henderson is right that the shattering of working-class and impoverished families is a tragedy. But how are we supposed to strengthen them, besides, as he suggests, adopting judgmental attitudes toward those who make the “wrong” decisions – regardless of why they make them? What good does it do to criticize education when attaining a degree is one of the factors most strongly correlated with having kids within wedlock and avoiding divorce?

Henderson dismisses all liberal activism as selfish, snobbish and misguided, and disregards activism in general – except when it’s calling for rigid social norms. But it’s not clear where that leaves him. Understanding why things happen is the minimal requirement for change, and yet Henderson is so invested in his outsider status that he alienates those who might want to see and learn from his perspective.

As I got older, my attitude toward the Occupy protests evolved. Just as Henderson had to scale the Ivory Tower before he could proclaim that a PhD isn’t a panacea for trauma, I had to land a well-paid job at Google to realize that the American Dream of upward mobility is built on an acceptance of poverty and extreme inequity. Only from the top could I see the lies that I had been sold while living at the bottom – and summon the energy to challenge them. If that makes me a hypocrite, so be it.

Emi Nietfeld is the author of “Acceptance,” a memoir of her journey through foster care and homelessness. After graduating from Harvard in 2015, she worked as a software engineer.

– – –

Troubled

A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social Class

By Rob Henderson

Gallery. 304 pp. $28.99

Catch up on the latest Boston.com Book Club pick and join the virtual author discussions.

Stay up to date with everything Boston. Receive the latest news and breaking updates, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.

Conversation

This discussion has ended. Please join elsewhere on Boston.com